I, Kant

The philosopher sailed to the edge of reason to discover 'what can I know?'

This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024). Next week: Mencius versus Xunzi

A WARNING: what follows is an impertinent attempt to distil in a few lines the essence of the philosophy of ‘mind’ of one of the greatest thinkers in the history of ideas, whose work has baffled generations of students and unrolled kilometres of impenetrable scholarship.

If our minds are sitting on the shoulders of this giant, at the very least we ought to consider a little of what he thought and wrote about the mind.

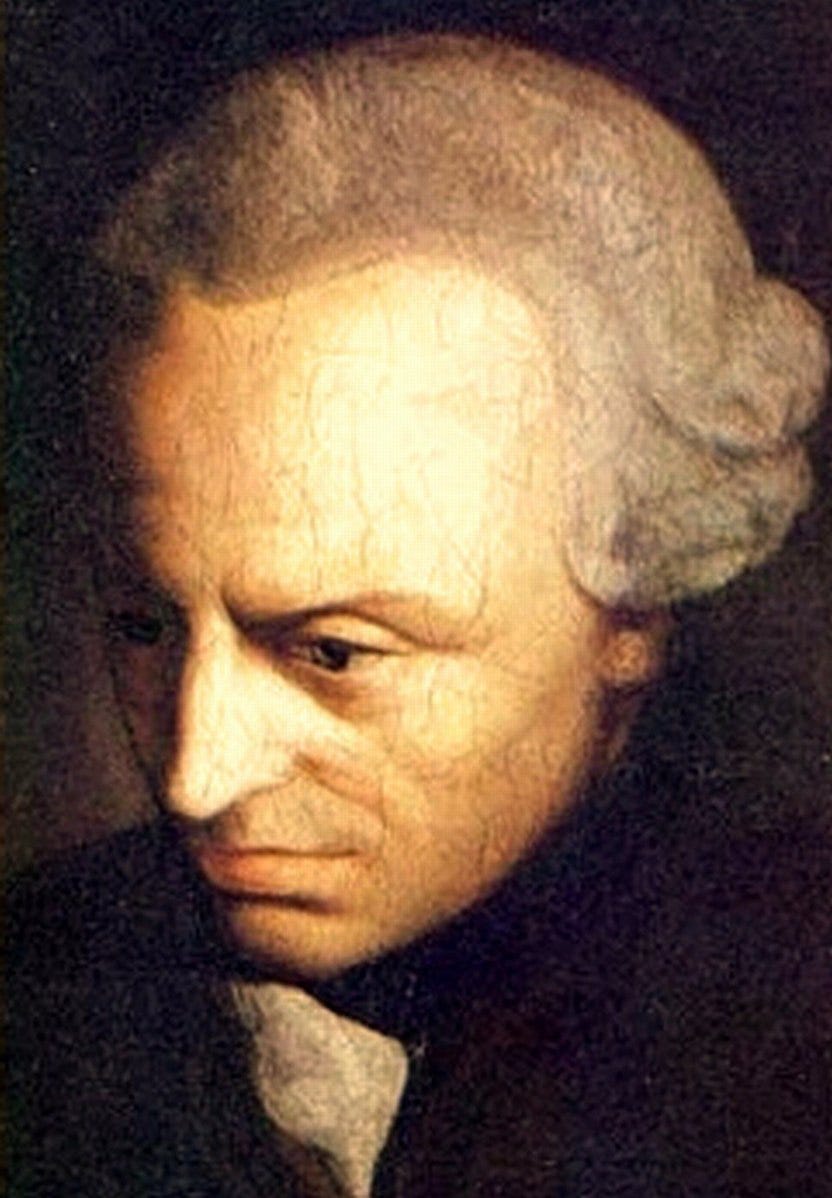

His name was Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and he was born in Königsberg, in East Prussia (today’s Kaliningrad, in Russia), the son of a harness-maker and the sixth of nine children. He grew up in a pietist Lutheran family, humble and devout, who took their Bible literally.

A prodigious student, at sixteen Kant entered the University of Königsberg and read Leibniz and Newton, among many others. His early essays proposed a theory of winds and examined the causes of the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. He rose to become a professor, lecturing in mathematics, philosophy, physics, metaphysics and geography. (He was the first academic to treat geography as a standalone subject.)

Kant was a man of precise habits, and his neighbours were said to set their watches by his daily regimen. Though he never married, he was a convivial spirit and a successful author. He did for our understanding of the mind what Copernicus had done for our understanding of the planet Earth: he redefined it.

Not everyone approved: Kant’s philosophical discoveries were ‘destructive, world-crushing thoughts’, wrote the German poet Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), who scornfully considered him a sort of philosophical ‘executioner’, who had, like Robespierre, presumed to judge or ‘weigh’ concepts beyond his station as a provincial bourgeois: ‘Nature had destined them to weigh coffee and sugar,’ Heine declared, ‘but Fate determined that they should weigh other things and placed on the scales of the one a king, on the scales of the other a god.’

Upon opening Kant’s The Critique of Pure Reason (1831), regarded as one of the greatest works of philosophy, I was tempted to give up. ‘I can’t,’ I thought. The lame pun amused and emboldened me. ‘Dammit, you can!’ I told myself. ‘And you must!’

Why? Because Kant’s conception of the ‘self’ or ‘mind’ or ‘soul’ (he used the terms interchangeably) is critical to our understanding of the limits of the human mind, and the frontiers of the world that Kant’s mind contained - and contains.

—

Kant’s ideas crackled to life in the fading embers of the Enlightenment, the period of history he himself had named. His writing is inaccessible to most of us, but moments reveal a crystalline clarity of intent.

His philosophy of mind posed three questions, which, he wrote, combined ‘all the interests of my reason’: ‘1. What can I know? 2. What should I do? 3. What may I hope?’

Kant’s answer to the first pulses through his entire philosophy, notably in The Critique of Pure Reason. This work addressed the problems posed by his three great predecessors: Am I the product of my experiences, as John Locke had argued? Is the world a mere impression or perception in my mind, as David Hume argued? Or can we intuit the world through inherent (a priori) reason, without recourse to experience, as Gottfried Leibniz suggested?

Kant came closer to answering those questions than any thinker before or since. His inquiry yielded one of the most important insights into human nature ever written: that a true understanding of our selves – that is, ‘self-knowledge’ – was possible only through the unity of a priori reason (knowledge we possess independent of our experiences, as if we were born with it) and a posteriori reason based on our empirical experience, or the evidence of our senses. Our knowledge and our judgements were thus a blend of nature and nurture, or inherent reason and knowledge gained through experience. The genius of Kant was to define the limits of a priori reason and the possibilities of a posteriori reason.

One way of looking at this is to take a simple, a priori judgement, such as ‘All bachelors are unmarried’. This is a useless tautology, empty of information, because all bachelors are, by definition, unmarried. The subject ‘bachelor’ and object ‘unmarried’ are self-eliminating. We intuit this through a priori reasoning. If we want to add to our knowledge of what it means to be a bachelor, we need to inquire and investigate them.

To gain meaningful information about the world, then, we need to make judgements that draw on both a priori and empirical knowledge: that is, knowledge gleaned from inherent reason and from our experiences of life. Kant dared to suggest that it was possible to show how we were capable of such judgements.

—

To do so, Kant first had to establish whether inherent (a priori) knowledge was possible. ‘For the chief question is always simply this,’ he asked, ‘what and how much can the understanding and reason know apart from all experience?’ That is, do we possess inherent powers of reason - a notion vehemently rejected by Locke?

To find out, Kant took a set of hedge trimmers to the mind. He pruned the outgrowths of experience, the ‘concepts’ that we derive from our exposure to life and ‘everything which belongs to sensation’.

What remained, he affirmed, was ‘pure intuition’, or ‘all that sensibility can supply a priori’.

His cerebral demarcation line produced two intuitions that, he reasoned, were innate in us all: our intuitions of space and time. These ‘two infinite things’ have no substance and yet ‘must be the necessary condition of the existence of all things’, Kant concluded.

Space and time share two attributes: they’re easily comprehensible as ‘finite’ elements of our daily existence, and they’re incomprehensible as ‘infinite’ dimensions of the cosmos.

We comprehend at once, ‘Let’s meet at the café (space) at 7 p.m. (time)’; but we cannot comprehend ‘Let’s meet in the next galaxy (space) in five millennia (time)’. That is, we know we live in space for a set time, but we have no conception of the actual dimensions of space and time. We live our lives on the threshold of space and time like divers on a familiar coral reef from which a vast ocean rolls away to an infinite depth and breadth.

Our sense that we exist in time and space is a priori, or innate in us, as Kant attempted to prove. He offered several propositions that were impossible to conceive and comprehend without our a priori intuition of space and time.

For example: ‘Every event has a cause’; ‘The world consists of enduring objects which exist independently of me’; and ‘All discoverable objects are in space and time’.

Kant concluded that our ability to comprehend such propositions must also be innately true of the human mind. They were a priori ‘synthetic’ judgements, or propositions that ‘cannot be established through experience’, as the philosopher Roger Scruton averred, ‘since their truth is presupposed in the interpretation of experience’. That is, they’re inherent ideas that expand our knowledge without recourse to any empirical investigation.

—

How was it possible, Kant asked, that our minds possess an intuition of space and time - and the propositions that flow from it - without any prior experience of them? Kant’s philosophy hinged on trying to answer that apparently unanswerable question.

Off the pages of The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) leap a string of marvellous neologisms that, like a pack of watchdogs guarding the gates to a maze that holds a sacred truth, see off all but the most stoic readers: ‘noumena’, ‘the categorical imperative’, ‘analytic and dialectic logic’, ‘paralogisms’, ‘a priori synthetic and a posteriori synthetic judgements’, and the withering ‘transcendental unity of apperception’.

Let’s tread carefully around a few of these ideas (we haven’t the space to explore them), chiefly their relation to Kant’s conception of the self.

Kant took Descartes’ equation ‘I think therefore I am’ and transformed it into a new conception of self. In Descartes’ version, the ‘thinking I’ is the subject and the ‘existing I’ is the object: I exist because I’m thinking.

Kant reformulated the equation: if a thinking thing – ‘I’ – is capable of thought, Kant asked, who is this ‘I’ who thinks? Does the facility of ‘thought’ render ‘me’ conscious and create my experience? Is there an ‘I’ – yours, mine – to whom the state of thinking belongs? Can we ever know the ‘thing in itself’ that thinks?

As Kant wrote: ‘I do not know myself through being conscious of myself as thinking [Descartes’ proposition], but only when I am conscious of the intuition of myself as determined with respect to the function of thought.’

He described as ‘apperception’ our awareness of ourselves as an ‘I’ who thinks. Thus, ‘I’ am conscious of, or can ‘apperceive’, my ‘self’. Or: ‘I’ am a ‘thinking thing’ called Paul Ham – but, as Kant might have asked, who or what is the ‘I’ that apperceives the ‘thinking thing’ called Paul Ham?

‘The whole difficulty,’ Kant wrote, ‘is how a subject can inwardly intuit itself . . .’ He meant that it is impossible to know the nature of my conscious ‘I’ by recourse to the thoughts and experiences to which that ‘I’ attaches itself in life. Simply put, just because I can think (about stuff) doesn’t tell me anything about ‘me’, the mysterious ‘I’ that can intuit, or apperceive, my thinking mind.

Descartes’ great insight starts to dissolve under Kant’s gaze. ‘I think’ served merely to introduce ‘all our thought, as belonging to consciousness’. To reframe the question: whose consciousness? Kant answered that when ‘I’ think, this ‘voice of self-consciousness’ must be an innate expression of my ‘self’, because it is impossible to represent this thinking being, ‘I’, through any external (empirical) experience.

So my conscious ‘I’ is inherent, a priori. I was born with an ‘I’. That is, the ‘I’ in ‘I think’ is a ‘being’ that exists innately, an ‘object of inner sense’, which Kant called the self – or, to go the full Kant, the ‘transcendental object of inner sense’. (A thought, idea or argument is ‘transcendental’ in the Kantian sense if it ‘transcends’ the limits of empirical inquiry, and only exists inherently, in a priori conditions.)

That is to say, the innate self exists independent of life’s experiences and thus cannot be their subject. And that’s what Kant also meant by the ‘rational doctrine of the soul’, in which the innate self is ‘the absolute subject of all my possible judgments, and this representation of myself cannot be employed as predicate of any other thing’.

—

Let’s briefly reprise Kant’s other questions: what should I do? And what may I hope?

Dogged readers may be familiar with Kant’s ‘categorical imperative’, an exhortation commanding the will to ‘act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law’. Seemingly innocuous at first sight, the ‘imperative’ was a moral law that universalised the will by obliging a person to act as though everyone was bound by a law governing that action.

Perhaps this worked as a disincentive to commit crimes, but one can think of many instances where the imperative would not be conducive to moral harmony. If telling the truth should be a universal law, you would not be able to lie to save a friend. And if you thought it imperative to kill the enemy in wartime, you would outlaw conscientious objection.

Kant’s moral imperative seems a pale rival to the Golden Rule to ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’, as espoused by all the great religions. Yet he placed it at the centre of a just and decent society:

‘Morality, and humanity so far as it is capable of morality, is the only thing which has worth. Skill and diligence in work have a market price; wit, lively imagination and humour have a fancy price; but fidelity to promises and kindness based on principle (not on instinct) have an intrinsic worth.’

What might we hope? Of the nature of God, the origin of the world and the immortality of the soul Kant had little to say, conceding that the nature of the soul, in its metaphysical and religious senses, was beyond the scope of his investigation: ‘My soul . . . cannot indeed be known by means of speculative reason (and still less through empirical observation).’

That is, knowledge of the soul was neither innate not acquirable through experience. Thus, we are neither born with an idea of our souls, nor are we able to form one in our lives. So, asking if we believe in our own soul is the same as asking whether we believe in God: it is a question of blind faith.

Next Thursday, 21st November 2024: Mencius versus Xunzi

Selected sources and further reading:

Descartes, R. (2017) Collected Works of René Descartes, Hastings UK: Delphi Classics.

Hanna, R. (2008) ‘Kant in the Twentieth Century’ in Moran, D. (ed.) The Routledge Companion to Twentieth Century Philosophy, London: Routledge.

Heine, H. and Pollack-Milgate, H. (transl.) (2007) On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, I and Humphrey, T. (transl.) (1992) An Answer to the Question: What Is Enlightenment? Indianapolis IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Kant, I. and Ellington, J.W. (transl.) (1993) Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals: With, On a Supposed Right to Lie Because of Philanthropic Concerns, Indianapolis IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Kant, I. and Kemp Smith, N. (transl.) (1929) Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, London: Macmillan.

Kant, I. (2016) The Collected Works of Immanuel Kant, Hastings UK: Delphi Classics.

Kenny, A. (2006) An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Kitcher, P. (October 1982) ‘Kant’s Paralogisms’, The Philosophical Review, 91(4), pp. 515–47.

Scruton, R. (2001) Kant: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.