This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024).

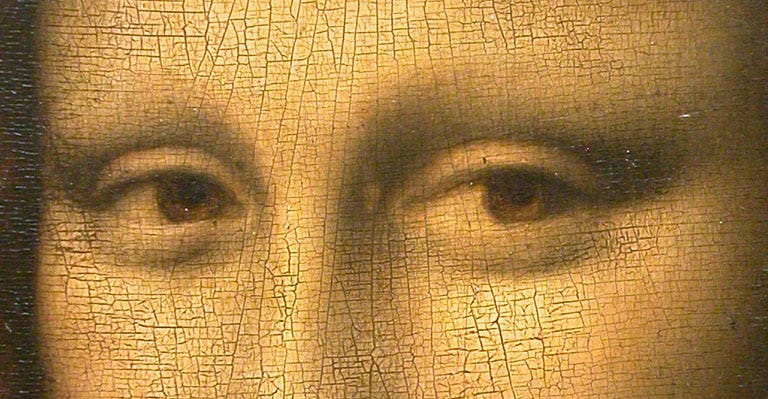

I RETURN with a sense of relief to my share of mediocrity, to the metronomic rhythm of my daily life, after contemplating Michelangelo’s Pietà (1498–99). Or Da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–91). Or listening to Schubert’s String Quintet. Or experiencing works of art that have transformed my relations with the world.

They’re a painful reminder of the chasm between transcendent beauty and the earth on which I live - a state of psychic discord eased by my proximity to the beautiful visual art of Susan Bottrell.

This strangely painful sensation inspired by works of art we love has the paradoxical effect of intensifying our longing for them. They diffuse the quotidian squalor.…