This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024). Join the journey!

Next Thursday: ‘If you kill us, we shall enter Paradise’

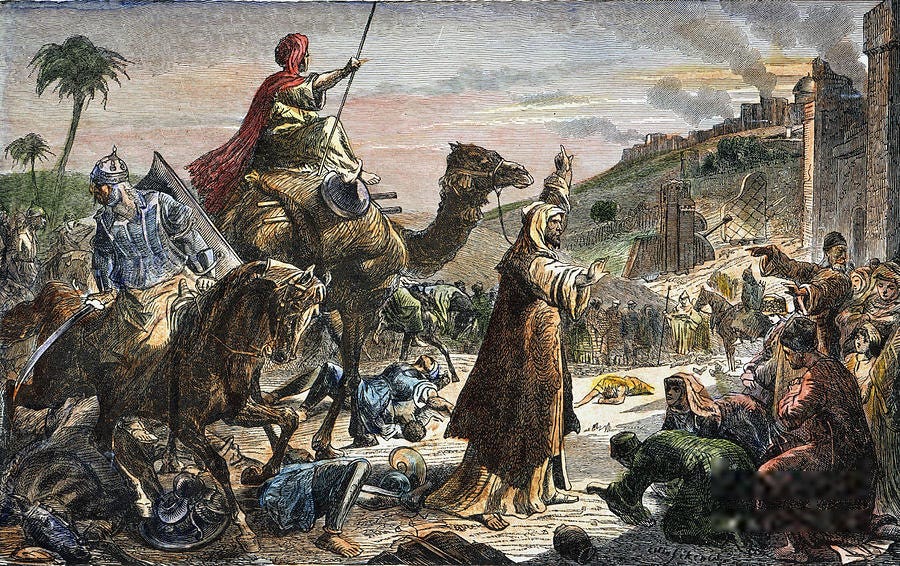

BY 641 CE ALL THE LEVANT was in Muslim hands except Jerusalem.

Of all the battles fought in the bloody decades to come – over the blazing flatlands of Iraq and Syria, by sea against Constantinople, along the North African coast and deep into southern Spain – none would antagonise the Christian mind so much as the loss of the Holy City to the Muslims.

The surrender of Jerusalem would drive a spear through the heart of Christendom and inspire Christian vengeance four centuries later in the form of the Crusades.

The Arab conquest of Jerusalem (636–638 CE) was of inestimable religious and symbolic value to the Muslims.

From Jerusalem, Muhammad was believed to have flown his Night Journey to hear the revelations of God.

Towards Jerusalem the first Muslims knelt in prayer (before Muhammad changed the direction to Mecca).

And Muslim leaders around this time were sharply attuned to the value of Jerusalem as the most sacred site for Jews and Christians, the scene of mass pilgrimage and home of the true cross, the Church of the Resurrection and the Jewish Temple (the latter, destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE, was now a Byzantine rubbish dump).

—

Sophronius, the surly Greek patriarch who ruled Jerusalem, warned the emperor Heraclius of the threat of the ‘Saracen’ in a letter sent in 634 CE.

Hoping the emperor would ‘break the pride of the barbarians’ who, ‘on account of our sins, have now risen up against us’, Sophronius bewailed the loss of Bethlehem to the Saracens, who had prevented the town’s Christians from celebrating Christmas in Christ’s birthplace.

‘As once that of the Philistine, so now the army of the godless Saracens has captured the divine Bethlehem,’ he lamented.

—

The Muslim siege of Jerusalem lasted two years.

As the people starved inside the city walls, Sophronius felt moved to deliver a sermon.

A man of great learning, he looked upon the Saracens as Bedouin riffraff, a vulgar people. Their appearance around the city walls roused him to deliver a thundering rebuke of the Arabs and a plea for God’s forgiveness.

The Arab invasion, he preached, was a sign of God’s anger at Christian iniquity.

‘Whence multiply barbarian invasions?’ he fumed. ‘Whence rise up the ranks of the Saracens against us? . . . Whence is the cross mocked? Whence is Christ Himself, the giver of all good things and our provider of light, blasphemed by barbarian mouths?’

God’s vengeance explained the conquest of Jerusalem by Islam: ‘The Saracens have risen up unexpectedly against us because of our sins and ravaged everything with violent and beastly impulse and with impious and ungodly boldness.’

—

The Muslim occupation of Jerusalem presented a model for what was soon to descend on countless communities throughout the Levant, North Africa, Transoxiana and Spain.

The second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab (c. 582–644 CE), assured the people living in the conquered city that their lives and property were safe, and they were free to practise their faith on condition that they paid the poll tax, as this extract from his decree makes clear:

‘Umar, the Commander of the Faithful, has granted to the people of Jerusalem . . . an assurance of safety for themselves, for their property, their churches, their crosses, the sick and the healthy of the city, and for all the rituals that belong to their religion. Their churches will not be inhabited [by Muslims] and will not be destroyed. Neither they, nor the land on which they stand, nor their cross, nor their property will be damaged. They will not be forcibly converted. No Jew will live with them in Jerusalem. The people of Jerusalem must pay the poll tax like the people of the [other] cities, and they must expel the Byzantines and the robbers. As for those who will leave the city, their lives and property will be safe until they reach their place of safety; and as for those who remain, they will be safe.’

Umar was true to his word. The caliph entered the city on a donkey (or camel) dressed in coarse, dirty robes, ‘perhaps in deliberate contrast to the lavish parades favoured by the defeated Byzantines’, the scholar Christopher Tyerman noted.

Umar left the Church of the Holy Sepulchre intact, and even prayed to Allah on a rug outside.

—

There followed the fall of Egypt (639–642 CE), judged the fastest capitulation to the forces of Islam by a Byzantine Christian territory.

The Coptic army, little more than a police force, were outgeneralled and out-fought.

The Arabs starved the garrison of ‘Babylon’ (the future Cairo) into submission and slaughtered anyone who refused to surrender.

When the militia defending Oxyrhynchus (the future Al-Bahnasa), south-west of Cairo, dared to resist, the Muslims massacred every man, woman and child they found in the little town, according to one resistance leader.

The conquest of Egypt was over in a matter of weeks, handing the Arabs some of the most fertile farming land in the world – Egypt being the former granary of the Roman Empire – with which to feed their armies.

Again, the Arabs allowed the survivors to live freely and worship as they pleased, so long as they paid the jizya, or tribute, and recognised the supremacy of Islam.

The Coptic Church survived Islamic rule, thanks to the heroic role of Pope Benjamin I of Alexandria, a prelate of boundless courage and diplomacy, whose body was eventually laid to rest in the monastery of Saint Macarius in 662 CE, where he is revered as a saint to this day.

—

The Christians responded to the shocking arrival of Islam with horror, grief and a plea for God’s forgiveness.

They beheld in the terrifying cry of ‘the Saracen’ the wrath of God and punishment for their sins. For many, the ascendancy of Islam was a sign of the Apocalypse.

A slew of poems expressed the turmoil and guilt of the Christian soul during and after these conquests.

One seventh-century Christian mourned the imminent obliteration of every living creature: men, women, children, animals, forests, plants. Whole cities would be razed, he wrote:

‘Regions will lie desolate without anyone passing through: the land will be defiled by blood and deprived of its produce.’

—

Around 637 CE, in a blank page of his Bible, an anonymous Syriac Christian jotted down his impressions of the Arabs at war (he was referring to their victory at the Battle of the Yarmuk).

The barely legible scrap is the earliest surviving Christian impression of jihad, and a terrifying premonition of what was to come:

‘Muhammad . . . priest, Mar Elijah . . . and they came . . . and . . . the Romans [fled] . . . And in January [the people] of Emesa received assurances for their lives. Many villages were destroyed through the killing by [the Arabs of] Muhammad . . . many people were killed, [of] the Romans about fifty thousand . . .’

While the Byzantines were unlikely to have suffered 50,000 casualties, the fragment hints at the scale of and terror inspired by the Arab war machine.

In his last speech to his people, Abu Bakr speculated about how Islam would one day acquire an empire:

‘Today you live in an age succeeding that of prophecy, at a fork in the path of pilgrimage. After me you will see despotic rule, deviant rule, a bold community, bloodshed . . . So cling to the places of prayer and take the Qur’an as your counsel. Hold fast to obedience and do not abandon unity . . . And then, just as the nearer lands have been opened to you, so too will the further lands.’

By the end of the Arab conquests, half the world’s Christians would be living under Muslim rule or would have converted to Islam.

Next Thursday, 5th June 2025: ‘If you kill us, we shall enter Paradise’

Selected sources and further reading:

Ansary, T. (2010) Destiny Disrupted: A History of the World through Islamic Eyes, New York: PublicAffairs.

Fazlur, R. (2020) Islam, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Griffith, S.H. (2007) The Church in the Shadow of the Mosque: Christians and Muslims in the World of Islam, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hodgson, M.G.S. (1977) The Venture of Islam (Vols. 1–3), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kaegi, W.E. (1992) Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, H. (2007) The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Kirby, P. (2003) ‘External References to Islam’, Christian Origins.

Mackintosh-Smith, T. (2019) Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes and Empires, New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Nicolle, D. (2009) The Great Islamic Conquests AD 632–750, Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

Penn, M.P. (ed.) (2015) When Christians First Met Muslims – A Sourcebook of the Earliest Syriac Writings on Islam, Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Peters, F.E. (2005) The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition, Volume I: The Peoples of God, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pseudo-Methodius and Garstad, B. (transl.) (2012) Apocalypse of Pseudo–Methodius: An Alexandrian World Chronicle, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Sizgorich, T. (October 2007) ‘“Do Prophets Come with a Sword?” Conquest, Empire, and Historical Narrative in the Early Islamic World’, The American Historical Review, 112(4), pp. 993–1015.

Sophronius and Allen, P. (transl.) (2009) Sophronius of Jerusalem and Seventh-Century Heresy: The Synodical Letter and Other Documents, Oxford: Oxford Early Christian Texts.

Tyerman, C. (2006) God’s War: A New History of the Crusades, London: Penguin Books.

Thanks Grant.

Much appreciated!

Very pleased to hear you're enjoying the book...

Cheers

Paul

Great post, thanks Paul, on an event that isn't well enough remembered or understood nowadays. I'm currently enjoying your book.