Kindling for the Reformation

When Gutenberg first printed the 'Word of God', Rome felt the fury of an oppressed people who knew they'd been deceived for centuries

This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024). Join our journey!

Next Thursday: The smoke of Purgatory

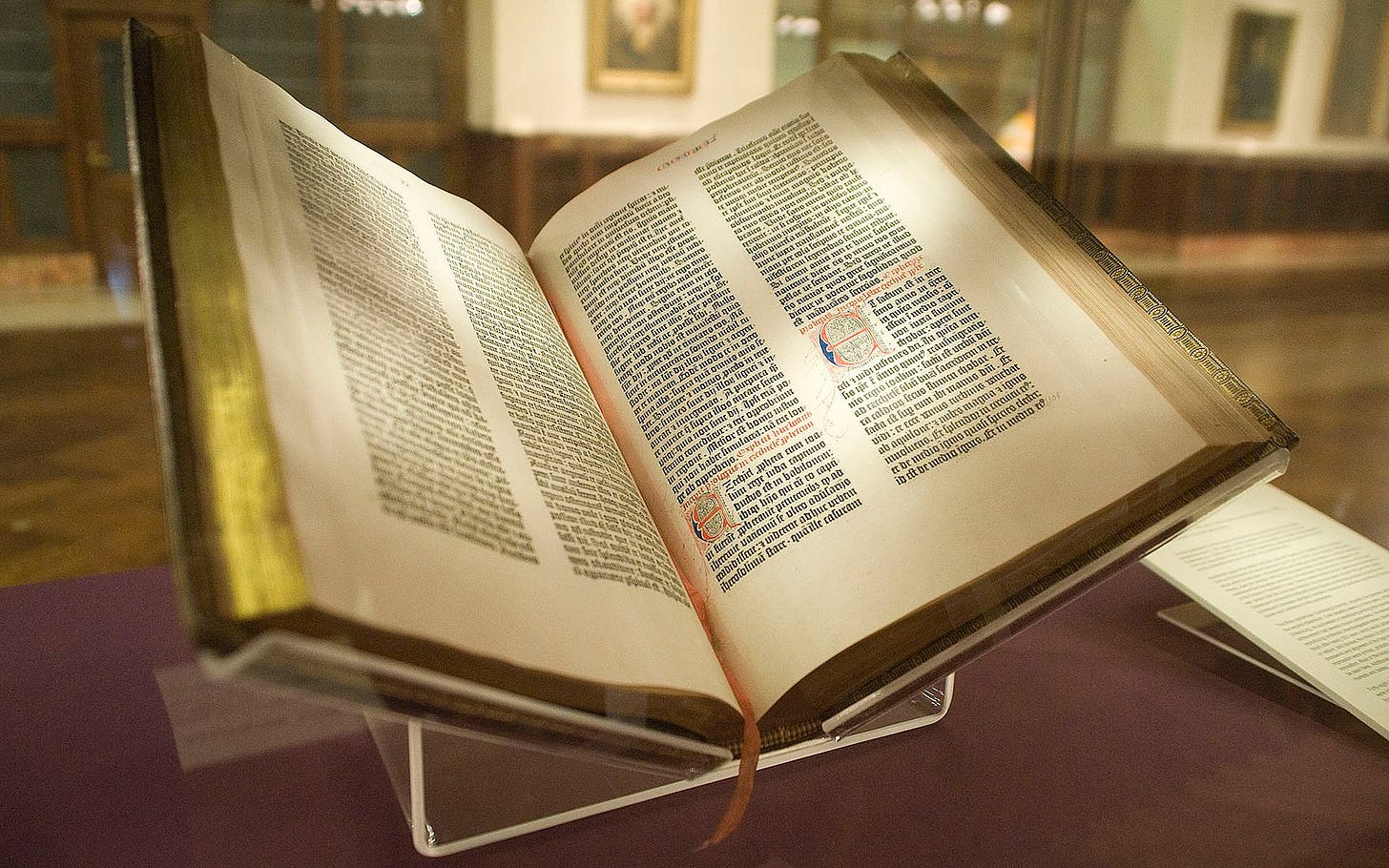

IN 1454-55 A BIBLE WAS PRINTED, on paper, in Mainz, Germany.

The Bible was the first book printed by movable type on Johannes Gutenberg’s newly invented printing machine.

Between 1466 and 1522, twenty-two editions of the Bible in High or Low German were published.

The first Italian Bible appeared in 1471; the first in Dutch in 1477; the Spanish and Czech versions in 1478; and in 1473 four French publishers produced the first abridged Bibles. The first English translation of the complete Bible appeared in 1535.

Since more people could read than write, there was great demand for the printed Bible. The first printing presses not only delivered the word of God to poorer communities, they also rapidly accelerated the spread of literacy.

Until then, most people had only heard extracts of the Bible chosen and read for them in Latin by their local priests. Few had had any idea of what was being read to them.

Now, for the first time, people were able to read the Bible in their own tongue, at home or in church reading groups.

And what they read astonished them. Here were the gospels in full; here, Christ’s miracles and parables and the unforgettable Sermon on the Mount. Here were stories of Christ’s compassion for the poor and forgotten (he even visited leper colonies!); here, Christ’s rejection of earthly power and wealth. And here were Saint Paul’s epistles, the Acts of the Apostles and the terrifying Book of Revelation.

—

Reading of Christ’s love of the poor and wretched, people dared to wonder: where is Christ’s love in our own miserable lives? Why have we been denied it? Surely the Bible’s lessons are everyone’s to share, and not a mystery reserved for popes and bishops and priests?

And the more they read, the more the people felt a jarring discord between the compassion offered by the biblical Christ and the brutal world in which they lived.

The holy book openly contradicted Catholic doctrine, subverting the very institution that claimed to have been built upon its words.

The faithful dared to question official church policy and to wonder at their relationship with God. To whom should they pray and confess? How should they worship? In whom should they place their faith – in Christ or in Rome?

The lessons of the parables and the Sermon on the Mount – where were they amid the rapacity of Rome? On whose authority was the pope’s word unarguable, his actions unimpeachable? Who had empowered the pope to speak for God?

Nowhere in the Bible did it name the pope as God’s representative on earth.

—

The pope would not officially declare himself ‘infallible’ until the First Vatican Council of 1869–70, but the roots of the idea of papal infallibility went back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The pope, as his pivotal role in the crusades has shown, had arrogated for himself the powers of the Almighty, to remit sins, to consecrate saints and martyrs, to absolve and to forgive.

The pope presumed to intercede on God’s behalf between Heaven and Earth. That doctrine ran counter to the teachings of Christ. In fact, the Catholic Church had perverted Christ’s message, cried the voices demanding reform.

To these voices Rome turned a tin ear. The Church refused to enact any of the recommendations put before the Fifth Lateran Council (convoked by Pope Julius II between 1512 and 1517), which would have limited papal power.

This tepid convocation of cardinals and bishops was held at a time of acute frustration with the ancient church, exacerbated by the spread of the printed Bible.

The French had just defeated the Papal States and the Spanish at the Battle of Ravenna (1512) and the authority of Julius – the ‘warrior pope’, who had named himself after Caesar – was irreparably damaged.

The council’s proposals focused on narrow academic issues of little relevance to the people’s fresh spiritual needs fermented by their reading the ‘Word of God’.

The council ended by denouncing ‘every proposition contrary to the truth of the enlightened Christian faith’ – in other words, any reform that challenged the authority of Rome. Instead, God, his ‘Almighty Creator’, had apparently authorised the pope to intercede on God’s behalf and redirect dissenting souls back to the church, for they were weak and misguided and required ‘healing’.

—

Although indifferent to the voices demanding reform, the Catholic bishops were feverishly attentive to the menace from within, namely heresy and paganism.

Rome would ‘purify’ rather than reform itself.

The purification of the faith followed a long and brutal tradition, nowhere more thoroughly than in Spain. Let’s backtrack a little, to understand why.

The Christian reconquest of Spain accelerated in 1086, when King Alfonso VI declared that he would restore Toledo to Christian control.

The Moors who had ruled Toledo for 376 years were to be expelled, enacting the assertion of Gregory VII, in 1073, that Spain ‘from ancient times belonged to St Peter’, and ‘it belongs even now . . . to no mortal but solely to the Apostolic see’.

Throughout Andalusia, the Muslims were about to pay for their occupation. Of hateful memory were the Almoravids, an austere sect of Berber Muslims who had invaded southern Spain in 1089, compelling Pope Urban II to launch a crusade.

Of unforgotten memory was the vizier al-Mansur, who had sacked many southern Spanish cities and who, in 997 CE, had fitted the mosque at Cordoba with the bells he’d stolen from the basilica of Saint James at Compostela.

—

Spain’s determination to eradicate the Muslims emboldened Rome to cleanse the faith of other ‘blasphemous’ sects: in the monasteries and universities, among the poor and dispossessed, or simply among those fed up with the tax burden of the church.

Hussites, Cathars, spiritualists and other sects were to be executed or exiled.

In his papal bulls of March 1208, Pope Innocent III justified this bloody stand against ‘heresy’ as a way of purifying the church: ‘[T]he perverters of our souls have become also the destroyers of our flesh,’ he proclaimed.

The church awarded itself near limitless powers to destroy anyone who so much as whispered against the papacy.

Konrad von Marburg, a German nobleman and priest, initiated with papal approval in the early twelfth century a savage campaign against heresy, chiefly witchcraft, in Thuringia and Hesse.

He and his thugs tortured and executed innumerable blameless people, dispatching their souls ‘to Hell’ on papal authority, without any semblance of a trial, until a gang of assassins mercifully killed the brute.

Pope Gregory IX nonetheless validated Konrad’s rampage as defending the purity of the faith.

—

In a similar spirit of pious sadism, Arnaud Amalric (c. 1160–1225), the papal legate who led the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars in Languedoc, in southern France, in the early thirteenth century, oversaw the extermination of an estimated 7000–14,000 people during the Massacre at Béziers.

The entire population were killed and the city razed, after which Amalric proudly wrote to Pope Innocent III in August 1209: ‘Our men spared no one, irrespective of rank, sex or age, and put to the sword almost 20,000 people. After this great slaughter the whole city was despoiled and burned, as divine vengeance miraculously raged against it.’

The diabolical Bernard of Cazenac and his vicious wife Elise launched a reign of terror in the Dordogne Valley around 1214. They deemed the Benedictine abbey of Sarlat a hothouse of Catharism. Rather than kill the monks and nuns, they mutilated them: 150 men and women had their hands and feet cut off or their eyes put out, as the historian Christopher Tyerman records:

‘Elise specialized in removing women’s thumbs to prevent them working and ordering the nipples of the poorest peasant women to be ripped off,’ denying them the ability to suckle their infants.

Why were the Cathars targeted in this way? They believed that Satan had created the material world and imprisoned the souls of angels in human bodies. Not until those angelic souls were free to reunite with their guardian spirits in Heaven would the spiritual and material worlds be restored to their rightful, separate places in the cosmos.

This was a loathsome heresy in the eyes of Rome, but the Albigensian Crusade failed to eradicate the French Cathars.

—

In time, the popes deemed covert, inquisitorial methods preferable to bursts of frenzied violence, and persuasion under torture would achieve the goals that had eluded the crusaders.

The eradication of heresy would henceforth be a job for the ‘inquisitor’.

A taste for violent suppression, however, had infected the body politic of the Roman church. Five crusades were fought against the Hussites of Bohemia (in 1420, 1421, 1422, 1431 and 1465–71).

The Hussites were fundamentalists who were greatly inspired by John Wycliffe, the radical English reformer. They took their name from their founder, Jan Hus (1370–1415), a heroic Prague academic who was burned alive by the Council of Constance.

—

Amid all these unconscionable acts approved by Rome, the expulsion of the Iberian Jewish community was unusually depraved.

The destruction of an entire society purely on the grounds of their religious belief had not yet defaced the annals of the church.

The Alhambra Decree, issued on 31 March 1492 by the Spanish Catholic monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, called for all practising Jews to leave Spain. Most had lived there since ancient Roman times.

Spain claimed the expulsion of some 100,000 Jews would remove the risk of them persuading the ‘conversos ’ – about 200,000 Jews who had converted to Catholicism to escape persecution and who remained living in Spain – to revert to Judaism.

—

The mass conversion of Spanish Jews to Christianity began in the late fourteenth century. The violent rhetoric of Ferrand Martinez, the archdeacon of Ecija, set the tone, writes the historian Simon Schama: in 1378 Martinez urged his congregations in southern Castile to attack the Jews ‘wherever and whenever you can’. Tear down their synagogues – the ‘houses of Satan’ – and burn their holy texts. Those ‘who frequented these sties of devilry’ were to be offered a simple choice: instant conversion or death.

In 1391, a wave of anti-Jewish preaching set in train the slaughter of about a third of the Iberian Jews and the forced conversion of another third.

These ‘New Christians’ (conversos or Marranos) were, like the former Muslims or moriscos, treated with suspicion and brutally scapegoated.

Some conversos were the least tolerant of their former faith. Jerónimo de Santa Fe (1400–1430), a physician and Spanish Jew who became a Christian, warned local rabbis that if they refused to convert, ‘ye shall be devoured with the sword’.

Jerónimo pointedly quoted Isaiah here, because Christians believed Isaiah was the prophet of Christ.

A new kind of inquisition was instituted by Queen Isabella around this time, to flush out any Jews and Muslims hiding behind their converso status. Interrogation and torture would force them to confess where their true loyalties lay.

When Granada fell to Christianity in 1492, and all of Spain was at last in Christian hands, Isabella gave the Castilian Jews an ultimatum: convert or be expelled.

Between 70,000 and 100,000 Jews chose exile rather than to convert. They spread across Europe, and later the world, forming the Sephardic Jewish diaspora (from the Hebrew word Sefarad, or ‘Spain’).

—

Meanwhile, Islam was on the march. Their target: Byzantium, and its shimmering city of Constantinople.

For centuries Islam had cherished this beauty on the Bosporus, the capital of both the Holy Roman Empire and the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Possession of Constantinople not only had great symbolic value in the Islamic world; it was also said to fulfil a prophecy traceable to Muhammad that Muslims loved to quote: ‘One day Constantinople will certainly be conquered. A good emir and a good army will be able to accomplish this.’

The Seljuk Turks who besieged the city were not ‘holy warriors’ in the earlier Arab tradition. The Seljuks were motivated more by plunder and capturing slaves than by a desire to convert the city to Islam. For many of them, profit trumped the Prophet.

They were well-fitted to the task, having proven themselves the most tenacious fighters of the Turkmen tribes who seasonally raided the frontiers of Christendom.

Nor were the Muslim and Christian realms irreconcilably divided by ‘faith’ at this time, as historian Caroline Finkel shows. Many peacefully coexisted. Both entered alliances with the other when it suited them. Christian warriors even fought in Seljuk ranks.

—

The conquest of Byzantium was less a Holy War in Turkish eyes than a traditional battle over treasure – in this case, the richest on Earth.

John VIII Palaiologus, the emperor in Constantinople, hoped the Turkish threat would unite the Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic churches in the common defence of Christendom.

Unity was John’s dream, and he was not above begging Rome for help when the Muslims threatened his city.

Rome had exacted a heavy price for aid. A succession of popes had demanded nothing less than Byzantium’s complete renunciation of Orthodox belief as a precondition for military assistance.

In 1369, for example, the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologus promised to observe certain Catholic rites if the pope would send military help against the Turks; John received papal assurances but no help.

Emperor John VIII Palaiologus would also be disappointed, because of Orthodox opposition to Rome’s demands. In 1439 he consented to the union of the Greek and Roman churches, but the Council of Florence that year, which he attended with 700 supporters, failed to bridge the divide.

The most critical theological issues splitting the Orthodox East and Latin West remained the use of leavened or unleavened bread in Communion; the Latin doctrine of Purgatory (not accepted by the Orthodox); and the matter of papal supremacy (unrecognised by the Orthodox). The threat to Constantinople was well down the agenda.

—

In the end, the union of East and West failed due to Byzantine opposition. With Christendom irreconcilably divided and little to lose, in 1453 the twenty-one-year-old sultan of the Ottomans, Mehmed II, besieged Constantinople, determined to possess the richest relic of the enfeebled Byzantine Empire and fulfil Muhammad’s prophecy.

After a fifty-three-day siege, Mehmed’s heavy artillery and naval supremacy overwhelmed the forces of the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, whose bankrupt and corrupt city had never recovered from the Fourth Crusade and its occupation by the Latin church.

Constantine again begged the pope for help, offering to reform Orthodox belief in line with Roman Catholic doctrine if Rome sent military aid. Rome refused, such was the sensitivity of the centuries-old schism between the two branches of Christendom.

Constantinople fell to the Ottomans on 29 May 1453, ending 1100 years of Christian rule, dating from its consecration by Constantine the Great in 330 CE.

Hagia Sophia, the greatest Christian cathedral and wonder of Byzantine architecture that had stood in the city since 537 CE, was converted into a mosque and the Byzantine Empire, such as it was (most of Greece, Thrace and Macedonia) dissolved.

Western Christendom reacted to the loss of Constantinople by promising further violence. Pope Nicholas V called for a new crusade, and issued a papal bull, Etsi ecclesia Christi, in September 1453.

He offered gifts of indulgences, salvation, and temporal and eternal glory to anyone who helped rid Constantinople of the Turks. He miserably failed.

Those ‘gifts’ were the very papal ‘excesses’ that Martin Luther’s revolt in 1517 would try to eradicate. The crowning irony was that the coming Reformation, borne along by the printed Bible and the people’s piercing demands for reform, would break the Roman Catholic Church from within.

Next Thursday, 18th September 2025: The smoke of Purgatory

Selected sources and further reading:

Emerton, E. (ed.) (1990) The Correspondence of Gregory VII, New York: Columbia University Press.

‘Fifth Lateran Council, Sessions 1–X11 (1512–1517)’, Catholic Profession of Faith.

Finkel, C. (2012) Osman’s Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire 1300–1923, London: John Murray.

MacCulloch, D. (2004) Reformation: Europe’s House Divided, 1490–1700, London: Penguin Books.

Migne, J-P. (ed.) (1844) ‘Arnaud Amalric to Innocent III, August 1209’, Patrologia Cursus Completus, Series Latina, 216(139).

Moore, R.I. (2012) The War on Heresy: Faith and Power in Medieval Europe, London: Profile Books.

O’Callaghan, J.F. (2004) Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

Papal Encyclicals: https://www.papalencyclicals.net/.

Pegg, M.G. (2005) The Corruption of Angels: The Great Inquisition of 1245–1246, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Po-Chia Hsia, R. (ed.) (2004) A Companion to the Reformation World, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Pomponazzi, P. and Gontier, T. (transl.) (2012) Traité de l’immortalité de l’âme / Tractatus de immortalitate animae, Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Powell, M.E. (2009) Papal Infallibility: A Protestant Evaluation of an Ecumenical Issue, Grand Rapids MI: William. B. Eerdmans.

Richards, J. (1990) Sex, Dissidence and Damnation: Minority Groups in the Middle Ages, London: Routledge.

Schama, S. (2013) The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words (1000 BCE – 1492), London: The Bodley Head.

Tierney, B. (1972) ‘Origins of Papal Infallibility, 1150–1350: a Study on the Concepts of Infallibility, Sovereignty and Tradition in the Middle Ages’, The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 25(01), pp. 94–8.

Tyerman, C. (2006) God’s War: A New History of the Crusades, London: Penguin Books.