This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024). Join the journey!

Next Thursday: Killer popes

ONE JUNE DAY IN 793 CE, while the monks of the monastery of Lindisfarne – on ‘Holy Island’, off the Northumbrian coast of Britain – were going about their daily rituals, a galley drew up on the shore nearby.

The seaman who disembarked were known to the monastery: the fur-clad, waterborne heathens had been here before, presumably to trade. The English cleric and scholar Alcuin even remarked on their appealing hairstyles.

This time, though, the hairy pagans had one purpose in mind: to slaughter the monks and sack the monastery.

The savagery the ‘Norsemen’ unleashed upon Lindisfarne spared no one: the monks were butchered, tossed into the sea or enslaved, and their monastery plundered. The marauders made off with the church plate.

The raid’s unprovoked ferocity and indiscriminate slaughter were unprecedented in British monastic history. No political or religious motive seemed to drive the raiders, and they made no attempt to negotiate or state terms.

It was a massacre of the Christians but it might have been anyone; the victims’ faith didn’t matter.

As Alcuin wrote in a letter to the Prince of Northumberland:

‘Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold, the church of St Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as prey to pagan peoples.’

The Anglo-Saxons had had earlier contacts with the Norsemen. Danish ships had arrived off the Dorset coast near Weymouth around 789 CE, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

Lindisfarne was the first full-scale raid, portrayed as the apocalyptic culmination of ‘fierce foreboding omens’ – storms, lightning, whirlwinds, ‘fiery dragons’ and famine – until ‘the ravaging of wretched heathen men destroyed God’s church at Lindisfarne’.

—

Out of the northern lights they came, borne on great ships, landing in Britain and France, on the Baltic coast and further south.

What began as a series of summer raids on isolated communities turned, by the mid eighth century, into massed invasions by the ‘Vikings’ (literally ‘pirates’), who, drawn to warmer, richer climes, preferred to stay and winter in their vanquished territories.

In time, the Viking campaigns of the ninth and tenth centuries ‘would shatter the political structures of western Europe’, in the view of Neil Price, one of the great historians of the Viking Age.

We can easily dispense with the tiresome myth of the Vikings as noble warriors who observed codes of honour, tolerance and restraint.

Nor were they peaceful shepherds and traders who kept the home fires burning, tending their pigs and sheep and rarely venturing further than the fjord, as some have suggested.

The survival of those peaceful Norse communities, if they existed at all, relied on the unprovoked violence of their seaborne husbands, fathers and brothers.

The Vikings were uniquely barbaric because their actions were driven by a theology that predetermined the destruction of the Earth. The world was going to die, ran the Viking mantra, so we might as well plunder it and enjoy it while it lasts.

That belief animated their zest for conquest, bloodshed and booty.

Let’s remind ourselves what a Viking raid meant. In Price’s words, behind every arrow that described a Norse fleet on the map of Europe lay…

‘…[an] urgent present of panic and terror, of slashing blades and sharp points, of sudden pain and open wounds; of bodies by the wayside, and orphaned children; of women raped and all manner of people enslaved; of entire family lines ending in blood; of screams and then silence where there should be lively noise; of burning buildings and ruin; of economic loss; of religious convictions overturned in a moment and replaced with humiliation and rage; of roads choked with refugees as columns of smoke rose behind them. Of utter, ruthless brutality, expressed in all its forms.’

—

By 830 CE, fleets bearing thousands of Norsemen were landing in Britain and mainland Europe.

They ploughed up the Thames, the Loire, the Seine, the Danube and the Rhine.

They travelled overland as far as the Slavic steppes and the beginnings of the Silk Road.

By 874 CE, every English kingdom but one – Wessex – was in Scandinavian hands.

Further west they would reach the American continent in 1021, 470 years before Christopher Columbus.

War for the Norsemen was a frame of mind, a belief system, a ritual act and, of course, a livelihood. War was, in sum, a ‘lifestyle’.

The slaughter during a Viking invasion – of the elderly, the innocent, women and children – exceeded in scale and ferocity that in any previous European conflict.

The Romans, Greeks and Muslims aimed to absorb, govern, tax or enslave their colonies, not to annihilate them. Even the Gothic invaders were no strangers to clemency.

The Vikings’ brutality was not ‘normal Dark Age activity’, asserts the historian Sarah Foot.

Witness the Vikings on a rampage in the Loire Valley, in 860 CE, as described by Ermentarius of Noirmoutier, a monk the Norsemen had driven from his monastery:

‘Everywhere the Christians are the victims of massacres, burnings, plunderings: the Vikings conquer all in their path and nothing resists them: they seize Bordeaux, Périgeux, Limoges, Angoulême and Toulouse. Angers, Tours and Orléans are annihilated . . . Rouen is laid waste, plundered and burned: Paris, Beauvais and Meaux taken, Melun’s strong fortress levelled to the ground, Chartres occupied, Evreux and Bayeux plundered, and every town besieged.’

—

In 845 CE, the Vikings hung 111 Frankish prisoners as a sacrifice to Odin, the chief Norse god, and to terrify the locals.

On 29 March about 120 Viking ships bearing 5000 warriors besieged Paris, burning down its walls, ransacking the city and slaughtering many occupants.

After attacking Hamburg and other riverside cities, the Vikings sailed south, to Iberia, sacking Lisbon, Cádiz and Algeciras, before heading inland, up the Guadalquivir River, where they conquered Seville, killing all the men and enslaving the women and children, according to an eye-witness account by Ahmad al-Razi.

In the 860s, the Rus’, a Norse people originating from Sweden and Finland who had settled in the Baltic in the eighth century, conquered and were gradually assimilated by the indigenous Slavs, producing a mongrel ethnic group known as Russian and Belorussian.

This, like all Nordic assimilations – in Britain, Normandy and Germany – was a long and complicated process, beyond our scope to record in detail.

—

What motivated the fury of the Vikings? Were they beasts in human form, a diabolical force sent to punish sinners and wipe out Christendom?

Such questions baffled contemporary Christians. Doubtless the Norsemen who lived in what we now call Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Iceland were intent on seizing booty, women and slaves. But that explanation is inadequate. The truth lay in the psychological power of prophecy over the Norse mind.

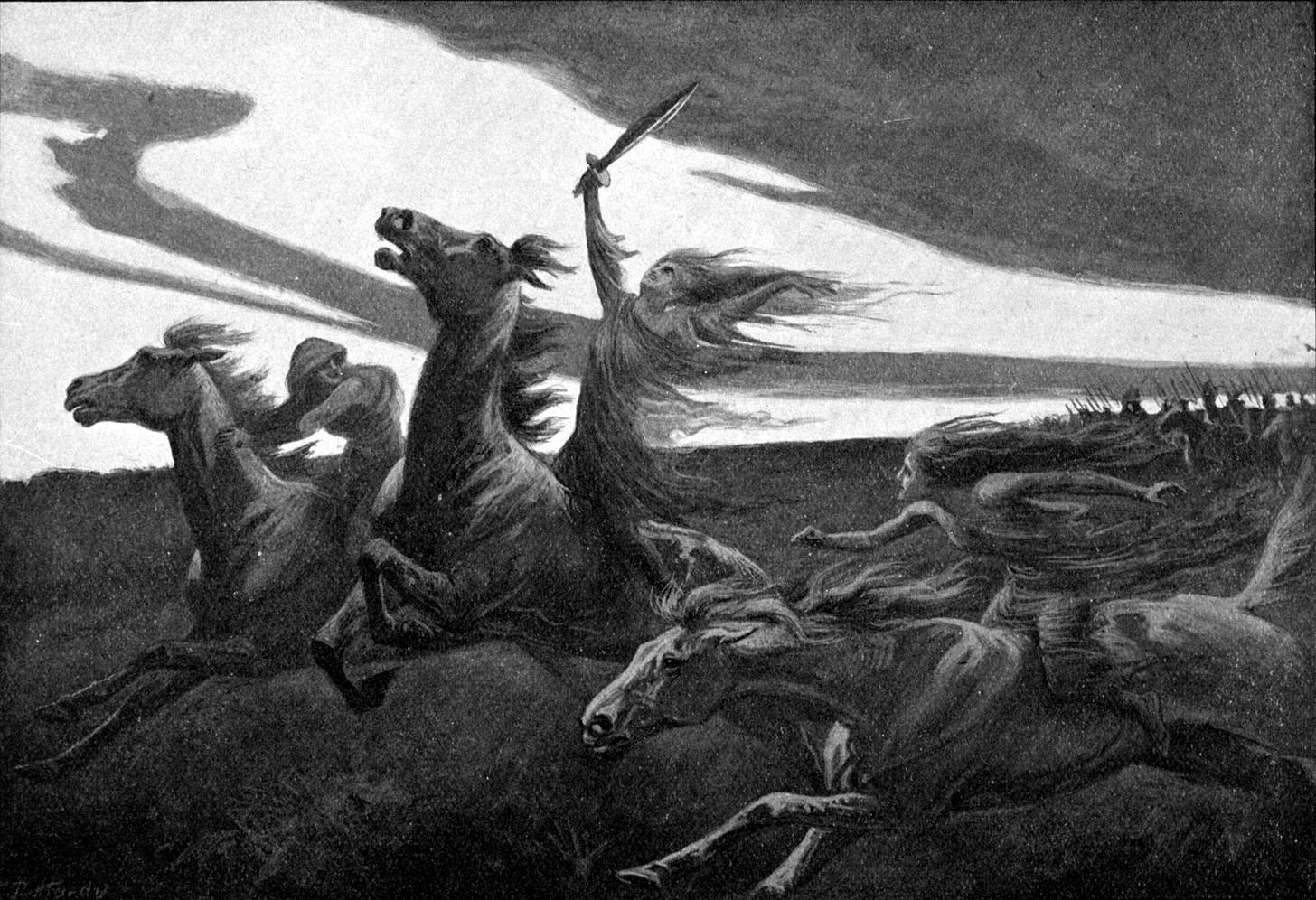

The Vikings believed that by ransacking the Earth, they were anticipating the awesome prophecies of Norse mythology, according to which all creation was preordained to die in the final battle of Ragnarök, when ‘wolves will swallow the sun and moon, the white-hot stars will sink into the sea and shroud the world in steam, the powers of the night will pour through a hole in the sky, and the gods will march to war for the last time’, as Price describes it.

This Nordic idea of the end times entailed the annihilation of every living thing, with no hope of redemption or salvation.

Not even the Norse gods would survive: the cataclysm would wipe out the entire pantheon of sixty-six deities, the most important of whom were one-eyed Odin, hammer-wielding Thor and the trickster Loki, as well as the formidable goddesses Frigg, Freyja and Hel.

‘The Vikings,’ Price tells us, ‘created one of the few known world mythologies to include the pre-ordained and permanent ruin of all creation and all the powers that shaped it, with no lasting afterlife for anyone at all . . . Everything will burn at the Ragnarök, whatever gods and humans may do.’

Just two survivors of this apocalypse, Lif and Lifthrasir, would repopulate a purified world, the Norsemen believed.

—

All this was predestined in the Viking mind, according to Price:

‘The outcome of our actions, our fate, is already decided and therefore does not matter. What is important is the manner of our conduct as we go to meet it.’

That conduct would be brutal and uncompromising, as decreed by fate. Fate weighed heavily on Nordic consciousness because everything that happened was fated, whatever choices you made in real time.

The Norse gods had predetermined the fate of the Earth, and the destinies of every human being were woven on the looms of diabolical female creatures called norns.

In a battle poem called ‘The Web of Spears’ (in the Njáls saga), norn spirits were depicted operating a loom made of human body parts that wove the outcome of a battle.

After battle, female monsters called valkyries would sweep down and guide the souls of dead warriors to Valhalla.

Caught in this loom of fate, mere mortals had no power to arrest the march to destruction. The Vikings concluded that they should seize the treasures of the Earth while they could, before the last battle – Ragnarök – reduced everything to ash.

Their predestined doom did not inhibit the Vikings from practising an odd form of free will, within the limits of conquest, plunder and the satiation of their carnal desires.

‘Free will existed,’ notes Price, ‘but exercising it inevitably led to becoming the person you always, really, had been.’

Who had you been? Who would you be? In the Viking mind, you were always becoming.

You were becoming a man who would fulfil his potential on the battlefield, on the high seas, in the mead hall, in bed and among the conquered.

You were a body in whom dwelt a potential sailor, lover, drinker, killer.

Seen in this light, mercy, compassion, shame, guilt – the measures of character revered by Christians – had little traction in the minds of a people who believed it was their lot, indeed their destiny, to seize, sack, rape and enslave with impunity.

—

Slaves were the bedrock of the Viking economy. These poor wretches, or ‘thralls’, were bought and sold in the slave markets of Christendom and Islam, for whom bartering in human flesh was legal and widely practised.

Being seized, flung into a Viking galley and sold from port to port devastated the mind and body. One moment you thought of yourself as a human being with a soul, a family and a function; the next you were merely Viking property.

Thralls who got sick or too old were put down like dogs. Female thralls were raped by their owners at will, and their bodies shared among his friends.

A Muslim trader called Ahmad ibn Fadlan witnessed Viking slaveowners in the Volga in 922 CE gang-raping enslaved girls while their wives stood indifferently by.

‘Even at the point of sale, a woman was sometimes raped one last time in the presence of her purchaser,’ Price observes.

Thralls were swiftly reduced to listless creatures, with lifeless eyes and leathery skin, caked in mud.

Slaveowners gave their slaves nicknames that often mocked some physical defect – for example, Stout, Sticky, Badbreath, Stumpy, Fatty, Sluggish, Grizzled and Longlegs, for male slaves; or Stumpina, Dumpy, Bulgingcalves, Bellowsnose, Shouty, Bondwoman, Greatgossip and Raggedyhips, for female ones.

Unlike Christians and Muslims, the Vikings didn’t bother to convert their vassals to the Norse religion, or to force them to pay homage to Odin, Thor, Loki and the rest of the gods. Odin did not demand the death of those who refused to believe in him.

—

Notwithstanding their barbarity, the Vikings had a unique idea of the soul. Several ‘beings’ inhabited each Viking: the hamr (literally ‘skin’), meaning the shell or shape of the person; the flesh wrapping, or what we call the body; the hugr, his or her quality or ‘essence’ – the attributes of mind and spirit that made up one’s character.

Every Viking also possessed a hamingja and fylgja. Your hamingja (‘luck’) was a female guardian spirit who brought good fortune. To a people whose lives were preordained, the ‘lucky’ were fated to be lucky, and hence revered – until their luck ran out.

Your fylgja (‘follower’) was a feminine animal spirit that reflected your character, rather like the spiritual mascots in Philip Pullman’s fantasy series His Dark Materials.

A timid person’s fylgja might be a goat or a sheep, while the cunning or bold-hearted might have a snake, lion or eagle.

—

The Vikings believed their gods – chiefly Odin, Thor, Loki and Freyja, among thirteen major deities – were constantly meddling in their lives.

To appease them, the Norse communities engaged in monstrous sacrificial rites. They adorned their sacrificial grounds with a menagerie of body parts, animal and human, and strung up from trees entire carcasses of elks, bears and horses.

An obsession with human sacrifice animated Norse burial rites: the bodies of the highborn were put to rest at sea, in an orgy of rape and mutilation.

The form varied by region, but in essence the deceased’s favourite female thrall was passed among his comrades, who raped and inseminated her, each shouting out that he had ‘done his duty’.

Domestic animals were then hacked to pieces and their body parts tossed onto the boat and into the sea. The slave girl was then laid by the rotting corpse and further pack-raped, after which a sorceress stabbed her.

Next, a naked attendant set the blood-drenched bark alight and cast it adrift, bound for the great mead hall in the sky.

—

The deceased went first to ‘Hel’ – not a burning lake in the Christian sense but a high, draughty hall ruled by the goddess Hel, a blue-skinned creature, half-woman, half-corpse.

If worthy, the dead proceeded to Valhalla, an immense hall on a shimmering plain, tiled in golden shields, with spear rafters and chainmail upholstery.

All the important gods had their own, ethereal residences in which the dead might reside (until Ragnarök destroyed them), but Valhalla was the home of Odin. Nothing less would satisfy a warrior’s posthumous ambition than to reside there.

—

Exposed to the Christian faith in the countries they overran, the Vikings began to question their theology, and the cruelty, stupidity and fickleness of their gods.

Their Christian vassals had little interest in converting to the Viking religion, and this exacerbated the Vikings’ waning faith in their homegrown gods.

Unlike the religions of the conquered, theirs lacked a sacred text and a prophet or spiritual head. Worse, Viking theology had no concept of salvation, in the Christian and Muslim sense. Their gods were bloody and unhelpful.

So, the Vikings were open to spiritual renewal, rather like the German tribes who had converted en masse to Christianity, and gradually they warmed to a faith that promised not senseless destruction but eternal life.

The more they assimilated with the Christians, the more the Norsemen and women came over to Christ, either from the bottom up, through emulation and admiration, or from the top down, after the example of Christian kings, chiefs and priests.

And many Viking men married Christian women who turned their ears from the mayhem of Odin to the gentle entreaties of Christ.

By the eleventh century, most of Scandinavia and its possessions were either Christian or ‘Christianising’.

New runestones bore Christian inscriptions, such as ‘He died in Denmark in white baptismal clothes’ and ‘God help his soul’. Around 60 per cent of runestones found in Sweden mention Christianity and the people’s conversion.

In Uppland, the inscriptions on seventy-five runestones refer to the ‘bridges’ that bore the souls of the dead to Heaven.

The famous Jelling Stone of 970 CE carved under the direction of King Harald Bluetooth depicted the crucified Christ and commemorated the conversion of Denmark to Christianity. It was a perfect example of a faith conquering the souls of its conquerors.

Next Thursday, 10th July 2025: Killer popes

Selected sources and further reading:

Alcuin, ‘Letter of Alcuin to Ethelred (793)’, Raid on Lindisfarne 793, Historic English Research Records, Heritage Gateway, https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/Gateway/.

Alfred the Great and chroniclers, with Swanton, M.J. (transl.) (1998) The Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle, London: Routledge.

Brink, S. and Price, N. (eds) (2008) The Viking World, London: Routledge.

Clark, D. (2007) ‘Kin-slaying in the “Poetic Edda”: The End of the World?’, Viking and

Medieval Scandinavia, 3, pp. 21–41.

Cook, R. (ed. and transl.) Njal’s Saga, London: Penguin Classics.

Coupland, S. (2003), ‘The Vikings on the Continent in Myth and History’, History, 88(2), pp. 186–203.

Ellis, C., (December 2020) ‘Remembering the Vikings: Violence, Institutional Memory and the Instruments of History’, History Compass.

Fadlan, A.I. with Lunde, P. and Stone, C. (transls.) (2012) Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North, London: Penguin Classics.

Fidler, R. and Gíslason, K. Saga Land, Sydney: ABC Books.

Foot, S. (1996) ‘The Making of Angelcynn: English Identity before the Norman Conquest’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 6, pp. 25–49.

Garipzanov, I. and Bonte, R. (eds.) (2014) Conversion and Identity in the Viking Age, Turnhout Belgium: Brepols Publishers.

Morris, M. (2021) The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England: 400–1066, London: Hutchinson.

Nelson, J.L. (transl.) (1991) The Annals of St-Bertin, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Price, N. (2020) Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings, New York: Basic Books.

Price, N. (2019) The Viking Way: Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia, Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Sawyer, P.H. (1975) The Age of the Vikings, London: Hodder & Stoughton Educational.

Snorri, S. (2006) The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology, London: Penguin Classics.

Steinsland. G. et al (eds.) (2011) Ideology and Power in the Viking and Middle Ages: Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, Orkney and the Faeroes, Boston: Brill.

Thorsson, O. (2001) The Sagas of Icelanders, London: Penguin Books.

Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. (1975) Vikings in Francia, Reading UK: University of Reading.

Winroth, A. (2014) The Age of the Vikings, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

Winroth, A. (2014) The Conversion of Scandinavia: Vikings, Merchants, and Missionaries in the Remaking of Northern Europe, New Haven CT: Yale University Press.