Jesus the prophet

Christian theocrats claim Christ as their Messiah. Here's what they were supposed to have learned from the man they call the Son of God

This is Who made our minds?, my Thursday essay probing the greatest, cruellest and most beautiful minds of the past 5,000 years, inspired by my book, The Soul: A History of the Human Mind (Penguin 2024).

Next Thursday: Christ crucified (the 3rd of several essays on Christianity)

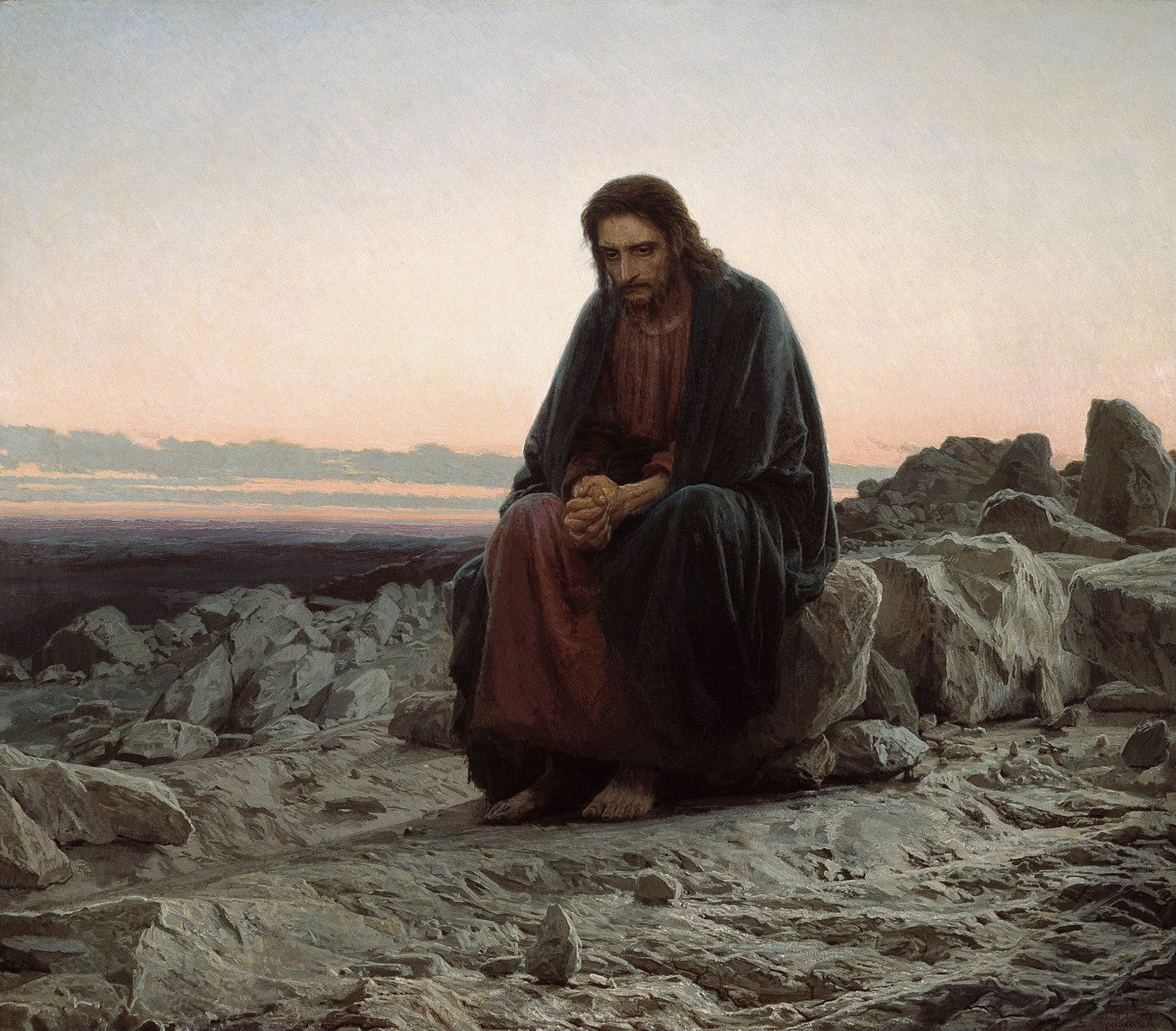

WHILE WANDERING Galilee, Jesus Christ taught his followers in parables and homilies that illustrated a moral or spiritual lesson.

His lessons were deeply felt by the people because they mirrored how the people lived.

The parables addressed social injustice, the meaning of faith, the quality of love and the value of prayer, using simple and familiar images. Hence the Parable of the Sower, the Parable of the Yeast, the Parable of the Good Samaritan and so on.

Some parables were mysterious and open to various readings; in Hebrew, the word ‘parable’ is often also used to mean ‘riddle’.

Jesus said that he had come to save the world, meaning the souls of us all, and to lead humankind into God’s grace. That involved teaching the mysteries of faith, love and compassion, and teaching by example.

So, he went about ‘doing good’ for the wretched of the Earth, many of whom had never felt the hand of compassion. He comforted the poor, the sick, the orphaned, the homeless and the mad.

In the front rank of Jesus’ compassion were the pariahs of society: the prodigal (meaning ‘wasteful’ or ‘reckless’) son, the tax collector, the prostitute.

The powerful were not his priority: the rich had as much chance of being admitted to Heaven, he said, ‘as of a camel passing through the eye of a needle’.

At the core of Christ’s teaching were three Golden Rules, three new commandments:

‘You shall love God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind’;

‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself’; and

‘Whatever you want men to do to you, do also to them.’

So, if you find qualities in yourself worthy of love, then you shall find and love those qualities in your family, your friend, your neighbour and strangers you meet.

If you expect others to treat you well, then treat them well. This inverted the negative Golden Rule of Confucius: ‘Do not do to your neighbour what is disagreeable to you.’

For Jesus Christ, ‘not harming’ others was a passive act and failed to encourage positive good; it seemed to exonerate ‘every sin which does not injure our neighbour’.

To love others as you would have them love you asked people to examine their own behaviour and their own consciences, Christ preached. If you want the truth, tell the truth; if you want peace, lay down your own weapons; if you expect respect, show respect; if you desire love, show love.

As Christ taught: ‘Judge not, and you shall not be judged. Condemn not, and you shall not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven. Give, and it will be given to you.’

It is impossible to overstate the revolutionary power of these ideas over his listeners.

The ‘Kingdom of God’ was not some ethereal palace in the sky, Jesus taught: it lived inside every person. For him, the Kingdom of God was the human conscience, the individual soul.

Asked mockingly by the Pharisees, ‘When will the kingdom of God come?’, Christ replied: ‘The kingdom of God is within you.’

That had never been said before. It silenced his detractors, for a while. None had heard of such an idea.

—

This ‘kingdom of conscience’, the human soul, would suffer damnation were it sold, corrupted or debauched, Christ taught: ‘And do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. But rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.’

Jesus asked his amazed disciples: ‘For what profit is it to a man if he gains the whole world, and loses his own soul? . . . Or what will a man give in exchange for his soul?’

Of what value were the laws of the Sanhedrin – the Jewish rabbinical court – or the power of the Roman Empire against such a vision? In the eternity of Heaven, Christ taught, they were worthless ephemera:

‘You do not know what manner of spirit you are of,’ Jesus told his disciples, according to the apostle Luke. ‘For the Son of man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.’ He had come ‘to reward each person according to what they have done’, wrote the apostle Matthew.

—

Of all Jesus’ exhortations, forgiveness seems the hardest for people to bear.

True believers should forgive their enemies, he taught. Very few do.

A grudging smile and a limp handshake seem the limit of most people’s magnanimity. Jesus insisted on the full grovel:

‘Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, and pray for those who spitefully use you. To him who strikes you on the one cheek, offer the other also. And from him who takes away your cloak, do not withhold your tunic either. Give to everyone who asks of you.’

So the next time you’re mugged and left bleeding on the road, with good grace give away whatever else you own and accept more punishment. Turn the other cheek.

How were his followers to apply such lessons to those who would massacre their families, burn their homes and kidnap their children? Like so many of Christ’s lessons, they pose unfathomable questions.

—

Jesus taught the importance of love for and care of children in particular – a lesson that remains painfully relevant today: ‘But whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in Me to sin, it would be better for him if a millstone were hung around his neck, and he were drowned in the depth of the sea.’

If this were carried out, the seabed would be littered with the bodies of priests and vicars and false prophets who have sexually abused children.

When Jesus’ disciples bickered over whose faith was strongest, their master rebuked them, saying, ‘If anyone desires to be first, he shall be last of all and servant of all.’

He then sat a little child beside him and said, ‘Whoever receives one of these little children in My name receives Me; and whoever receives Me, receives not Me but Him who sent Me.’

True faith, then, was characterised by a childlike innocence. True faith was not pretentious or ostentatious. In that lesson, Jesus anticipated the grotesque hypocrisy of the proud and powerful who would later claim to follow him.

—

The gospels record how those who witnessed Jesus teach recognised him as a prophet in the great Hebrew tradition.

When he touched the open coffin of the widow of Nain’s son, saying, ‘Young man, I say to you, arise!’ and the boy ‘sat up and began to speak’, the crowd fell back in fear, crying, ‘A great prophet has risen up among us.’

When Christ fed 5000 people with only five loaves and two fishes, sharing out ‘as much as they wanted’, those at the feast were amazed and said: ‘This is truly the Prophet who is to come into the world.’

When Jesus healed the sick, restored sight to the blind, exorcised the possessed, changed water into wine and performed other miracles, his fame grew, preceding his triumphal entry into Jerusalem astride a donkey, to celebrate Passover, an event Christians would commemorate as Palm Sunday.

The multitude already knew his name. ‘This is Jesus the prophet of Nazareth of Galilee,’ they cried.

—

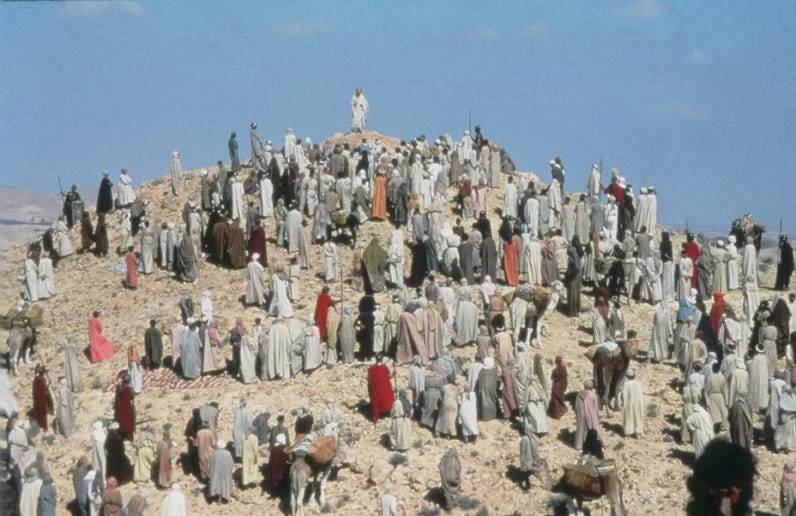

If any sermon or speech may be said to have changed the world forever, it was Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount (of Olives).

From the moment Christ opened his mouth, the people heard things they had never thought possible.

For the Sermon on the Mount prophesied a new world order. It raised the wretched of the Earth to the forefront of God’s favour. It repudiated the idea, prevalent at the time, that the poor, the weak, the sick and the victims of injustice were somehow to blame for their fate – that their lot was God’s punishment for their sins, much as Job’s friends had told him.

They did not deserve it, Jesus told them. God was not punishing them. God loved them. They were ‘blessed’.

No more would they suffer; no longer would they be ‘the last’. From that point they were ‘the first’, the righteous heirs of the Kingdom of Heaven.

It is worth repeating Jesus’ sermon here, for the like had never been said before:

‘Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are those who mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness: for they shall be filled.

Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called sons of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are you, when they revile and persecute you, and shall say all kinds of evil against you falsely for my sake.’

—

Christ’s vision of heavenly justice astonished and exalted the people, and confirmed the worst suspicions of the Pharisees: this man Jesus thought he was a prophet of God.

How dare this upstart, this mere carpenter, prophesise in the charismatic tradition of Moses, Elijah and Elisha, they raged.

Worse, Jesus had scorned their ancient Jewish customs. The laws of Moses were redundant, he had taught, and the rite of circumcision a mere performance.

Were all-comers, then, pagans and gentiles, circumcised and uncircumcised, welcome into the Christ sect, the rabbis wondered.

What Christ said next threw the high priests into an apoplectic fury, and sealed his fate. He declared that he was the living fulfilment of the Jewish laws and prophetic books: the Messiah, no less, whose coming Isaiah had prophesied:

‘Do not think that I have come to destroy the Law or the Prophets,’ he said. ‘I did not come to destroy but to fulfil.’

He warned sinners of the ‘end times’, or Judgement Day, as later recorded by Matthew, Mark and Luke: ‘But I say to you that it shall be more tolerable for the land of Sodom in the day of judgment than for you.’

Crucially, Jesus spoke of two resurrections – of the soul and of the body: ‘Let the dead bury their dead,’ he said, meaning that the dead in soul should bury the dead in body. ‘The hour is coming, and now is, when the dead shall hear the voice of the Son of God; and they that hear shall live.’

A parade of false prophets and natural disasters would herald the end of the world, Jesus warned:

‘For many will come in My name, saying, I am the Christ . . . [and] nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. And there will be famines, pestilences, and earthquakes in various places. All these are the beginning of sorrows. Then they will deliver you up to tribulation and kill you, and you will be hated by all nations for My name’s sake. And then many will be offended, will betray one another, and will hate one another. Then many false prophets will rise up and deceive many. And because lawlessness will abound, the love of many will grow cold. But he who endures to the end shall be saved.’

This litany of horrors would end with Christ’s return:

‘. . . the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken. Then the sign of the Son of Man will appear in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth . . . will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory.’

—

While Jesus’ prophetic powers enthralled his followers, the Pharisees resolved to destroy his sect. This man had dared work on the Sabbath and defy the Law of Moses.

Worse, Christ had declared the ‘old Jewish ways’ irrelevant to the question of salvation: to be received into God’s grace, Jesus dared to say, demanded inner faith and charity, not the fastidious adherence to Jewish ritual:

‘What does it profit, my brethren, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can faith save him? If a brother or sister is naked and destitute of daily food . . . but you do not give them the things which are needed for the body, what does it profit? Thus also faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead.’

But how would the Jewish authorities get rid of Jesus? John the Baptist had been easy, they recalled: beheaded by Herod in response to a whimsical request for his head from Salome, Herod’s daughter.

Jesus was in a different league. The crowds called him Hosanna, ‘the adored one’, their light and joy.

When the Pharisees ‘sought to lay hands on him’, Matthew noted, they feared the multitude, who ‘took him for a prophet’.

The Jewish priests would get to Jesus by appealing to the apostle Judas, whom they’d heard was disillusioned with Christ. It would take a lot more than 30 pieces of silver to persuade Judas to betray Jesus, as my essay on Judas’ motives explains.

—

By his example, Jesus inaugurated a moral revolution on the side of the poor, the weak, the disabled and the oppressed.

He never held himself up as an object for worship. He served God as a teacher, healer and prophet, a transmitter of the Word by example.

His church was meant to glorify God, not himself or the rabbis, or later, popes and cardinals and preachers in megachurches. His teaching was supposed to shepherd ordinary souls to salvation.

The simplicity and humility of the apostolic age would pass, and it is hard to imagine that the Biblical Jesus would have approved of what was to come.

The assertive ‘Christianity’ built by the apostles Saint Paul and Saint John in the second century CE would portray a Jesus of power: the saviour of the world, the object of mass veneration.

In time, billions of Christians would prostrate themselves before this idea of Christ, their idol and spiritual superstar, whose brilliance would outshine that of God himself.

—

Our astonishment at Jesus Christ lies not in whether he spoke the sermons or performed the miracles attributed to him.

It lies in the fact that billions of people believed he did.

They believed in him, and in his works, and the power of their faith has transformed the course of human history.

Napoleon would lament, before his death, on the isle of St Helena, that millions were ready to die for ‘the crucified Nazarene’, a man who had founded a spiritual empire based on love. But no one would die for Alexander, or Caesar, or himself. For they had founded earthly empires based on violence.

‘I know men,’ Napoleon reportedly said, ‘and I tell you, Christ was not a man. Everything about Christ astonishes me. His spirit overwhelms and confounds me. There is no comparison between him and any other being. He stands single and alone.’

Next Thursday, 6th March 2025: Christ crucified (3rd of several essays on Christianity)

Selected sources and further reading:

Abbott, J.S.C. (1855) The History of Napoleon Bonaparte, London: Sampson Low.

Allinson, R.E. (1985) ‘The Confucian Golden Rule: A Negative Formulation’, Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 12(3), pp. 305–15.

Augustine and Dyson, R.W. (transl. and ed.) (1998) The City of God Against the Pagans, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barton, S.C. and Brewer, T. (2021) The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels, Durham: University of Durham.

Confucius and Slingerland, E. (transl.) (2003) Analects, Indianapolis IN: Hackett Classics.

Esler, P.F. The Early Christian World (Vol I–II), London: Routledge.

Schaff, P. (2006) History of the Christian Church, Peabody MA: Hendrickson Publishers.

Schama, S. (2013) The Story of the Jews: Finding the Words (1000 BCE – 1492), London: The Bodley Head.

The Bible (New King James Version), Matthew 5:3–10, 5:17, 7:12, 10:15, 10:28, 16:24–28, 18:6; 21:46, 24; James 2:14–17; Mark 9:33–37, 12:29–31; Luke 6:27–37, 7:16, 9:55–56, 17: 20–21; John 6:14.

Vermes, G. (2013) Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea, AD 30–325, London: Penguin.

The Bible (New King James Version),

Vermes, G. (2013) Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea, AD 30–325, London:

Penguin.

Hi Peter

Thank you very much for your thoughtful and inspiring response to my latest essay.

I’m delighted to hear you’ll keep reading… hopefully to the end 🙏😅

We have a long way to go….stay with me, and I hope your friends find something worthwhile here too!

All the best

Paul

Hi Paul, This is the first piece of yours that I have read in full. Thank you. I am not a Christian or really “religious”, perhaps Daoist/Humanist, with a degree (1977) in “Drama & Religious Studies”. I studied RS because I was (still am) interested in the nature of mind and especially at that time “alternative states of consciousness” - which led to an interest in mysticism and psychology (my degree thesis was “Jungian Individuation and Tibetan Mandalas”). That is just some of my early leanings…

On reading this piece I found this section most helpful:

”To love others as you would have them love you asked people to examine their own behaviour and their own consciences, Christ preached. If you want the truth, tell the truth; if you want peace, lay down your own weapons; if you expect respect, show respect; if you desire love, show love.”

I am aware of The Golden Rule, to some extent too of the differing versions present in Chinese philosophy, yet had not understood the Jesus’ version in this simple and direct way. I had not considered this, yet it is quite obvious and, as you note, radical! Thank you. I will continue to reflect on this….I have also chosen to forward this, together with the link to your Substack, to others I know who may be equally affected!

Secondly, your erudition motivates me to continue to read more, both here and elsewhere, so thanks for that (implicit) nudge!